Wednesday, December 10, 2008

sojourner truth

once know as isabella buamfree, sojourner truth ran way with her youngest child to the north. she work as a servant for the van wagen family. she discovered that a member of the Dumont family had sold one of her children to slavery in Alabama. Since this son had been emancipated under New York Law, Isabella sued in court and won his return. Isabella experienced a religious conversion, moved to New York City and to a Methodist perfectionist commune, and there came under the influence of a religious prophet named Mathias. The commune fell apart a few years later, with allegations of sexual improprieties and even murder. Isabella herself was accused of poisoning, and sued successfully for libel. She continued as well during that time to work as a household servant. isabella changed her name to sojourner truth in 1843, believing that she was intructed by the holy spirt. In the late 1840s she connected with the abolitionist movement, becoming a popular speaker. In 1850, she also began speaking on woman suffrage. and spoke he most famous speach "ain't i a woman," in 1850. After the War ended, Sojourner Truth again spoke widely, advocating for some time a "Negro State" in the west. She spoke mainly to white audiences, and mostly on religion, "Negro" and women's rights, and on temperance, though immediately after the Civil War she tried to organize efforts to provide jobs for black refugees from the war. in 1883 sojourner truth died.

Tuesday, November 18, 2008

The full Backround of the purchase

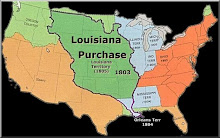

The central portion of North America was considered prime land for settlement in the early days of the republic. The Missouri and Red Rivers drained the region east of the Rocky Mountains into the massive Mississippi Valley, offering navigation and fertile farmlands, prairies, pastures and forests. The region also held large deposits of various minerals, which would come to be economic boons as well. Buffalo and other wild game were plentiful and offered an abundant food supply for the Native Americans who peopled the region as well as for later settlers.

From the mid-fifteenth century, France had claimed the Louisiana Territory. Its people constituted a strong French presence in the middle of North America. Always adamant in its desire for land, France engaged the British in the Seven Years' War (1754–1763; also known as the French and Indian war because of the alliance of these two groups against British troops) over property disputes in the Ohio Valley. As part of the settlement of the Seven Years' War, the 1763 Treaty of Paris called for France to turn over control of the Louisiana Territory (including New Orleans) to Spain as compensation for Spanish assistance to the French during the war.

By the early 1800s, Spain offered Americans free access to shipping on the Mississippi River and encouraged Americans to settle in the Louisiana Territory. President Thomas Jefferson officially frowned on this invitation, but privately hoped that many of his frontier-seeking citizens would indeed people the area owned by Spain. Like many Americans, Jefferson warily eyed the vast Louisiana Territory as a politically unstable place; he hoped that by increasing the American presence there, any potential war concerning the territory might be averted.

The Purchase

In 1802 it seemed that Jefferson's fears were well founded: the Spanish governor of New Orleans revoked Americans' privileges of shipping produce and other goods for export through his city. At the same time, American officials became aware of a secret treaty that had been negotiated and signed the previous year between Spain and France. This, the Treaty of San Ildefonso, provided a position of nobility for a minor Spanish royal in exchange for the return of the Louisiana Territory to the French.

Based on France's history of engaging in hostilities for land, Jefferson and other leaders were alarmed at this potential threat on the U.S. western border. While some Congressmen had begun to talk of taking New Orleans, Spain's control over the territory as a whole generally had been weak. Accordingly, in April 1802 Jefferson and other leaders instructed Robert R. Livingston, the U.S. minister to France, to attempt to purchase New Orleans for $2 million, a sum Congress quickly appropriated for the purpose.

In his initial approach to officials in Paris, Livingston was told that the French did not own New Orleans and thus could not sell it to the United States. However, Livingston quickly assured the negotiators that he had seen the Treaty of San Ildefonso and hinted that the United States might instead simply seize control of the city. With the two sides at an impasse, President Jefferson quickly sent Secretary of State James Monroe to Paris to join the negotiations.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821), who had come to power in France in 1799, planned in 1801 to use the fertile Mississippi Valley as a source of food and trade to supply a French empire in the New World. However, in 1801 Toussaint L'Ouverture led a slave revolt that eventually took control of Haiti and Hispaniola, the latter of which Napoleon had chosen as the seat of his Western empire. French armies under the leadership of Charles LeClerc attempted to regain control of Haiti in 1802; however, despite some successes, thousands of soldiers were lost in battle and to yellow fever. Realizing the futility of his plan, Napoleon abandoned his dreams for Hispaniola. As a result, he no longer had a need for the Louisiana Territory, and knew that his forces were insufficient to protect it from invasion. Furthermore, turning his attentions to European conquests, he recognized that his plans there would require an infusion of ready cash. Accordingly, Napoleon authorized his ministers to make a counteroffer to the Americans: instead of simply transferring the ownership of New Orleans, France would be willing to part with the entire Louisiana Territory.

Livingston and Monroe were stunned at his proposal. Congress quickly approved the purchase and authorized a bond issue to raise the necessary $15 million to complete the transaction. Documents effecting the transfer were signed on 30 April 1803, and the United States formally took possession of the region in ceremonies at St. Louis, Missouri on 20 December.

Consequences of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase has often been described as one of the greatest real estate deals in history. Despite this, there were some issues that concerned Americans of the day. First, many wondered how or if the United States could defend this massive addition to its land holdings. Many New Englanders worried about the effect the new addition might have on the balance of power in the nation. Further, Jefferson and Monroe struggled with the theoretical implications of the manner in which they carried out the purchase, particularly in light of Jefferson's previous heated battles with Alexander Hamilton concerning the interpretation of limits of constitutional and presidential powers. In the end, however, the desire to purchase the territory outweighed all of these practical and theoretical objections.

The increases in population, commerce, mining, and agriculture the Louisiana Purchase allowed worked to strengthen the nation as a whole. The opportunity for individuals and families to strike out into unsettled territory and create lives for themselves helped to foster the frontier spirit of independence, curiosity, and cooperation that have come to be associated with the American character.

The Purchase

In 1802 it seemed that Jefferson's fears were well founded: the Spanish governor of New Orleans revoked Americans' privileges of shipping produce and other goods for export through his city. At the same time, American officials became aware of a secret treaty that had been negotiated and signed the previous year between Spain and France. This, the Treaty of San Ildefonso, provided a position of nobility for a minor Spanish royal in exchange for the return of the Louisiana Territory to the French.

Based on France's history of engaging in hostilities for land, Jefferson and other leaders were alarmed at this potential threat on the U.S. western border. While some Congressmen had begun to talk of taking New Orleans, Spain's control over the territory as a whole generally had been weak. Accordingly, in April 1802 Jefferson and other leaders instructed Robert R. Livingston, the U.S. minister to France, to attempt to purchase New Orleans for $2 million, a sum Congress quickly appropriated for the purpose.

In his initial approach to officials in Paris, Livingston was told that the French did not own New Orleans and thus could not sell it to the United States. However, Livingston quickly assured the negotiators that he had seen the Treaty of San Ildefonso and hinted that the United States might instead simply seize control of the city. With the two sides at an impasse, President Jefferson quickly sent Secretary of State James Monroe to Paris to join the negotiations.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821), who had come to power in France in 1799, planned in 1801 to use the fertile Mississippi Valley as a source of food and trade to supply a French empire in the New World. However, in 1801 Toussaint L'Ouverture led a slave revolt that eventually took control of Haiti and Hispaniola, the latter of which Napoleon had chosen as the seat of his Western empire. French armies under the leadership of Charles LeClerc attempted to regain control of Haiti in 1802; however, despite some successes, thousands of soldiers were lost in battle and to yellow fever. Realizing the futility of his plan, Napoleon abandoned his dreams for Hispaniola. As a result, he no longer had a need for the Louisiana Territory, and knew that his forces were insufficient to protect it from invasion. Furthermore, turning his attentions to European conquests, he recognized that his plans there would require an infusion of ready cash. Accordingly, Napoleon authorized his ministers to make a counteroffer to the Americans: instead of simply transferring the ownership of New Orleans, France would be willing to part with the entire Louisiana Territory.

Livingston and Monroe were stunned at his proposal. Congress quickly approved the purchase and authorized a bond issue to raise the necessary $15 million to complete the transaction. Documents effecting the transfer were signed on 30 April 1803, and the United States formally took possession of the region in ceremonies at St. Louis, Missouri on 20 December.

Consequences of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase has often been described as one of the greatest real estate deals in history. Despite this, there were some issues that concerned Americans of the day. First, many wondered how or if the United States could defend this massive addition to its land holdings. Many New Englanders worried about the effect the new addition might have on the balance of power in the nation. Further, Jefferson and Monroe struggled with the theoretical implications of the manner in which they carried out the purchase, particularly in light of Jefferson's previous heated battles with Alexander Hamilton concerning the interpretation of limits of constitutional and presidential powers. In the end, however, the desire to purchase the territory outweighed all of these practical and theoretical objections.

The increases in population, commerce, mining, and agriculture the Louisiana Purchase allowed worked to strengthen the nation as a whole. The opportunity for individuals and families to strike out into unsettled territory and create lives for themselves helped to foster the frontier spirit of independence, curiosity, and cooperation that have come to be associated with the American character.

Bibliography

Ellis, Joseph J. American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson. New York: Knopf, 1997.

Kastor, Peter J., ed. The Louisiana Purchase: Emergence of an American Nation. Washington,

D.C: Congressional Quarterly Books, 2002.

Kennedy, Roger. Mr. Jefferson's Lost Cause: Land, Farmers, Slavery, and the Louisiana Purchase. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Labbé, Dolores Egger, ed. The Louisiana Purchase and Its Aftermath, 1800–1830. Lafayette: Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1998.

From the mid-fifteenth century, France had claimed the Louisiana Territory. Its people constituted a strong French presence in the middle of North America. Always adamant in its desire for land, France engaged the British in the Seven Years' War (1754–1763; also known as the French and Indian war because of the alliance of these two groups against British troops) over property disputes in the Ohio Valley. As part of the settlement of the Seven Years' War, the 1763 Treaty of Paris called for France to turn over control of the Louisiana Territory (including New Orleans) to Spain as compensation for Spanish assistance to the French during the war.

By the early 1800s, Spain offered Americans free access to shipping on the Mississippi River and encouraged Americans to settle in the Louisiana Territory. President Thomas Jefferson officially frowned on this invitation, but privately hoped that many of his frontier-seeking citizens would indeed people the area owned by Spain. Like many Americans, Jefferson warily eyed the vast Louisiana Territory as a politically unstable place; he hoped that by increasing the American presence there, any potential war concerning the territory might be averted.

The Purchase

In 1802 it seemed that Jefferson's fears were well founded: the Spanish governor of New Orleans revoked Americans' privileges of shipping produce and other goods for export through his city. At the same time, American officials became aware of a secret treaty that had been negotiated and signed the previous year between Spain and France. This, the Treaty of San Ildefonso, provided a position of nobility for a minor Spanish royal in exchange for the return of the Louisiana Territory to the French.

Based on France's history of engaging in hostilities for land, Jefferson and other leaders were alarmed at this potential threat on the U.S. western border. While some Congressmen had begun to talk of taking New Orleans, Spain's control over the territory as a whole generally had been weak. Accordingly, in April 1802 Jefferson and other leaders instructed Robert R. Livingston, the U.S. minister to France, to attempt to purchase New Orleans for $2 million, a sum Congress quickly appropriated for the purpose.

In his initial approach to officials in Paris, Livingston was told that the French did not own New Orleans and thus could not sell it to the United States. However, Livingston quickly assured the negotiators that he had seen the Treaty of San Ildefonso and hinted that the United States might instead simply seize control of the city. With the two sides at an impasse, President Jefferson quickly sent Secretary of State James Monroe to Paris to join the negotiations.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821), who had come to power in France in 1799, planned in 1801 to use the fertile Mississippi Valley as a source of food and trade to supply a French empire in the New World. However, in 1801 Toussaint L'Ouverture led a slave revolt that eventually took control of Haiti and Hispaniola, the latter of which Napoleon had chosen as the seat of his Western empire. French armies under the leadership of Charles LeClerc attempted to regain control of Haiti in 1802; however, despite some successes, thousands of soldiers were lost in battle and to yellow fever. Realizing the futility of his plan, Napoleon abandoned his dreams for Hispaniola. As a result, he no longer had a need for the Louisiana Territory, and knew that his forces were insufficient to protect it from invasion. Furthermore, turning his attentions to European conquests, he recognized that his plans there would require an infusion of ready cash. Accordingly, Napoleon authorized his ministers to make a counteroffer to the Americans: instead of simply transferring the ownership of New Orleans, France would be willing to part with the entire Louisiana Territory.

Livingston and Monroe were stunned at his proposal. Congress quickly approved the purchase and authorized a bond issue to raise the necessary $15 million to complete the transaction. Documents effecting the transfer were signed on 30 April 1803, and the United States formally took possession of the region in ceremonies at St. Louis, Missouri on 20 December.

Consequences of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase has often been described as one of the greatest real estate deals in history. Despite this, there were some issues that concerned Americans of the day. First, many wondered how or if the United States could defend this massive addition to its land holdings. Many New Englanders worried about the effect the new addition might have on the balance of power in the nation. Further, Jefferson and Monroe struggled with the theoretical implications of the manner in which they carried out the purchase, particularly in light of Jefferson's previous heated battles with Alexander Hamilton concerning the interpretation of limits of constitutional and presidential powers. In the end, however, the desire to purchase the territory outweighed all of these practical and theoretical objections.

The increases in population, commerce, mining, and agriculture the Louisiana Purchase allowed worked to strengthen the nation as a whole. The opportunity for individuals and families to strike out into unsettled territory and create lives for themselves helped to foster the frontier spirit of independence, curiosity, and cooperation that have come to be associated with the American character.

The Purchase

In 1802 it seemed that Jefferson's fears were well founded: the Spanish governor of New Orleans revoked Americans' privileges of shipping produce and other goods for export through his city. At the same time, American officials became aware of a secret treaty that had been negotiated and signed the previous year between Spain and France. This, the Treaty of San Ildefonso, provided a position of nobility for a minor Spanish royal in exchange for the return of the Louisiana Territory to the French.

Based on France's history of engaging in hostilities for land, Jefferson and other leaders were alarmed at this potential threat on the U.S. western border. While some Congressmen had begun to talk of taking New Orleans, Spain's control over the territory as a whole generally had been weak. Accordingly, in April 1802 Jefferson and other leaders instructed Robert R. Livingston, the U.S. minister to France, to attempt to purchase New Orleans for $2 million, a sum Congress quickly appropriated for the purpose.

In his initial approach to officials in Paris, Livingston was told that the French did not own New Orleans and thus could not sell it to the United States. However, Livingston quickly assured the negotiators that he had seen the Treaty of San Ildefonso and hinted that the United States might instead simply seize control of the city. With the two sides at an impasse, President Jefferson quickly sent Secretary of State James Monroe to Paris to join the negotiations.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821), who had come to power in France in 1799, planned in 1801 to use the fertile Mississippi Valley as a source of food and trade to supply a French empire in the New World. However, in 1801 Toussaint L'Ouverture led a slave revolt that eventually took control of Haiti and Hispaniola, the latter of which Napoleon had chosen as the seat of his Western empire. French armies under the leadership of Charles LeClerc attempted to regain control of Haiti in 1802; however, despite some successes, thousands of soldiers were lost in battle and to yellow fever. Realizing the futility of his plan, Napoleon abandoned his dreams for Hispaniola. As a result, he no longer had a need for the Louisiana Territory, and knew that his forces were insufficient to protect it from invasion. Furthermore, turning his attentions to European conquests, he recognized that his plans there would require an infusion of ready cash. Accordingly, Napoleon authorized his ministers to make a counteroffer to the Americans: instead of simply transferring the ownership of New Orleans, France would be willing to part with the entire Louisiana Territory.

Livingston and Monroe were stunned at his proposal. Congress quickly approved the purchase and authorized a bond issue to raise the necessary $15 million to complete the transaction. Documents effecting the transfer were signed on 30 April 1803, and the United States formally took possession of the region in ceremonies at St. Louis, Missouri on 20 December.

Consequences of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase has often been described as one of the greatest real estate deals in history. Despite this, there were some issues that concerned Americans of the day. First, many wondered how or if the United States could defend this massive addition to its land holdings. Many New Englanders worried about the effect the new addition might have on the balance of power in the nation. Further, Jefferson and Monroe struggled with the theoretical implications of the manner in which they carried out the purchase, particularly in light of Jefferson's previous heated battles with Alexander Hamilton concerning the interpretation of limits of constitutional and presidential powers. In the end, however, the desire to purchase the territory outweighed all of these practical and theoretical objections.

The increases in population, commerce, mining, and agriculture the Louisiana Purchase allowed worked to strengthen the nation as a whole. The opportunity for individuals and families to strike out into unsettled territory and create lives for themselves helped to foster the frontier spirit of independence, curiosity, and cooperation that have come to be associated with the American character.

Bibliography

Ellis, Joseph J. American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson. New York: Knopf, 1997.

Kastor, Peter J., ed. The Louisiana Purchase: Emergence of an American Nation. Washington,

D.C: Congressional Quarterly Books, 2002.

Kennedy, Roger. Mr. Jefferson's Lost Cause: Land, Farmers, Slavery, and the Louisiana Purchase. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Labbé, Dolores Egger, ed. The Louisiana Purchase and Its Aftermath, 1800–1830. Lafayette: Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1998.

The Great Deal in History

Gen. Horatio Gates to President Thomas Jefferson, July 18, 1803

Robert Livingston and James Monroe closed on the sweetest real estate deal of the millennium when they signed the Louisiana Purchase Treaty in Paris on April 30, 1803. They were authorized to pay France up to $10 million for the port of New Orleans and the Floridas. When offered the entire territory of Louisiana–an area larger than Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Portugal combined–the American negotiators swiftly agreed to a price of $15 million.

Although President Thomas Jefferson was a strict interpreter of the Constitution who wondered if the U.S. Government was authorized to acquire new territory, he was also a visionary who dreamed of an "empire for liberty" that would stretch across the entire continent. As Napoleon threatened to take back the offer, Jefferson squelched whatever doubts he had, submitted the treaty to Congress, and prepared to occupy a land of unimaginable riches.

The Louisiana Purchase added 828,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River to the United States. For roughly 4 cents an acre, the United States had purchased a territory whose natural resources amounted to a richness beyond anyone's wildest calculations.

National Archives and Records Administration http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/american_originals_iv/sections/louisiana_purchase_treaty.html

Robert Livingston and James Monroe closed on the sweetest real estate deal of the millennium when they signed the Louisiana Purchase Treaty in Paris on April 30, 1803. They were authorized to pay France up to $10 million for the port of New Orleans and the Floridas. When offered the entire territory of Louisiana–an area larger than Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Portugal combined–the American negotiators swiftly agreed to a price of $15 million.

Although President Thomas Jefferson was a strict interpreter of the Constitution who wondered if the U.S. Government was authorized to acquire new territory, he was also a visionary who dreamed of an "empire for liberty" that would stretch across the entire continent. As Napoleon threatened to take back the offer, Jefferson squelched whatever doubts he had, submitted the treaty to Congress, and prepared to occupy a land of unimaginable riches.

The Louisiana Purchase added 828,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River to the United States. For roughly 4 cents an acre, the United States had purchased a territory whose natural resources amounted to a richness beyond anyone's wildest calculations.

National Archives and Records Administration http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/american_originals_iv/sections/louisiana_purchase_treaty.html

Monday, November 17, 2008

The Brief Summary of The Louisiana Purchase

France' offer to sell the vast Louisiana Purcahse to the United States in 1803 sparked a constitutional dilemma. President Thomas Jefferson wanted to purchase the territory, which would double the size of the United States. But Jefferson also favored a narrow interpretation of the Constitution—and nowhere did it provide for acquiring additional territory. Because of the need to act quickly on the deal, there was no time to amend the Constitution. Instead, the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans in Congress passed legislation that gave the President permission to sign a treaty to receive the territory, and Congress appropriated the money to pay for it. Congress acted under the provision of the Constitution (Article 5, Section 3) that gave Congress the power to regulate the territories, arguing that that power included the right to purchase new territories. Congress and the President therefore stretched the Constitution to fit new circumstances and solve their dilemma.

Marshall Smelser, The Democratic Republic, 1801–1815 (New York: Harper & Row, 1968)

Marshall Smelser, The Democratic Republic, 1801–1815 (New York: Harper & Row, 1968)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)